By Marta Nieto Romero (in collaboration with Alessandro Vasta)

The other day I had an interesting conversation with my colleague Alessandro Vasta touching on the issue of Northern Europeans buying land in Portugal to set up sustainable projects. It made me think a lot on why am I suspicious about it, and we made interesting connections with his and my research. Please take it as an open reflection on how sustainability projects engage with their place (and share your thoughts with us!).

Abandonment or regeneration for non-humans?

Websites for buying land in Portugal are popping up here and there, and after the Eurovision success of Salvador Sobral this is just expected to grow in the coming years! 😀

There are many opportunities in interior Portugal to buy “abandoned” land (historically used for subsistence agrarian activities) as today almost all Portuguese population live near the coast. The word “abandonment” is charged with negative connotations. It seems then that land has to give something to humans in order to be worthy, and any activity that counter-acts abandonment is better than leaving land aside for natural regeneration.

Yet, many areas in Portugal are so degraded that they don’t need just “time for nature to do its work” but an active management to help the ecosystem to regenerate. The projects that I want to talk about in this post are hopefully doing just that: private organic farms or eco-tourism businesses, or sustainable living communities starting with private land but open to others to join to create a sustainable community. The latter could be seen, as it is in many cases, commoning communities: people trying to create community economies that prioritise ethical interdependence among people and with the planet (see Tamera ecovillage as a good example).

As a middle-class Spanish from Madrid, I completely share the purpose of these initiatives and consider them in principle good. Yet, seeing the growing popularity of Portugal and the rapid increase of foreigners moving in (maybe boosted because it’s cheap and sunny) makes me feel suspicious on whether these initiatives will bring about a positive change, and for whom.

I love Portugal, because of its distinct features: It has distinct landscapes, houses, people, dances, etc. How (if at all) can these projects incorporate and empower these features? How can they sustain the inherited stories and values of the places they borrow? How can they do it in a deep and valuable way, and not superficial? And most importantly, how can they be fair to communities that do not have access to the resources (material but also immaterial) that newcomers have?

Dis-placed innovative solutions?

I would be very sad if Portugal’s identity is erased in the future. Culture evolves, I know, and it is of course positive in many ways (if they would manage to regenerate the completely destroyed Portuguese forests for example). Yet, I feel that sometimes new sustainable initiatives come already with a fixed plan that doesn’t blend with the places where they land (in Alessandro’s words: “like a spaceship landing in a rural farm”). What if these initiatives tried to identify those traditional practices that have synergies with the aims of their projects? What if they tried to incorporate the history and the stories of the place to build a new and more sustainable culture? And also what if their presence would become a stimulating environment and deep sharing of knowledge and resources with the local communities?

In my view, this would be just fair, and an act of empathy with the local inhabitants that have survived the waves of emigration (because of political and economic reasons) and still live in rural Portugal. Yet, I believe it would be beneficial for supporting the kind of change that these projects aim at.

If the stories of the place are embedded within the newcomers’ projects (e.g. maintaining traditional festivities, refurbishing but maintaining the essence of houses, planting local varieties of plants, etc.) local inhabitants may empathise more with the project and can hopefully appreciate more their own identity and practices. Indeed, in general, Portuguese people are too humble and will always think foreign stuff is better than theirs. If more foreigners would use or recognise the value of local ways of doing, locals can become empowered to join existing initiatives or to lead an initiative themselves.

Commoning or exclusion?

The higher economic capacity of Northern Europeans, as compared to Portuguese, can be seen as one of the reasons that the latter is disadvantaged to create a projects like these by their own. It is true that in many cases, Portuguese do not even want to come back to the rural, as the rural is still seen as something to escape from in today’s society (and has negative connotations).

Almost every Portuguese I met has parents or grandparents growing food, owning chickens or animals… Thus, the idea of progress is to live in the city and not having to work the land to grow food (which is a hard physical work). The younger generation still has the negative connotation because of what their parents/grandparents endured (hard physical labour, not much possibility of education as most people had to help in the farm life), thus leading them to renounce this way of life. Yet, I believe that this will come at some point, but maybe when rural Portuguese distinct features have already been lost.

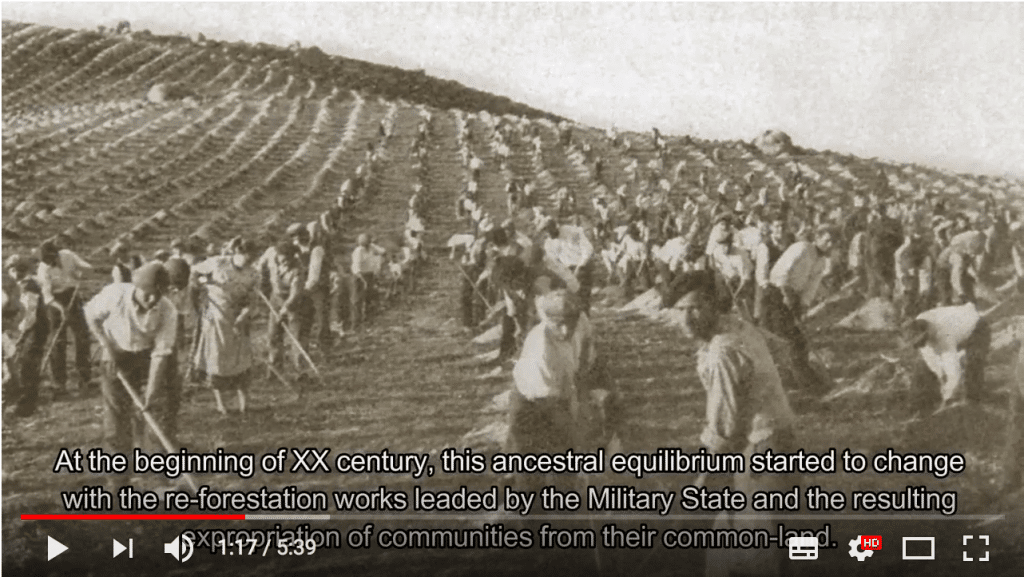

Additionally, those lands now in sale are the result of the waves of emigration due to poverty and industrialisation but also to the expropriation and reforestations of commonlands during last century. Commonlands were key for rural communities’ survival and when they were expropriated people had no access to land anymore, had to sell their livestock and emigrate to cities to get a waged job (watch the video below).

This made me reflect on an article I recently read about commoning in which Diprose et al. (2017) reflect upon questions of commoning vs. colonisation/exclusion:

“Responsiveness and responsibility to Indigenous people is a challenge to ‘progressive’ movements. For example, the Occupy movement’s ignorance of the fact that Turtle Island (North America) was already occupied illustrates the myopia of attempting to counter capitalism without addressing colonisation”- (Kelly in Diprose et al. 2017)

Any process of commoning implies an exclusion as well as an inclusion, since a commons always needs a community to care for it (Joanne in Diprose, 2017). Thus, the fact of creating a (sustainable) community raises political questions on who is included and excluded (Diprose, 2016; 2017).

I understand completely these kind of projects and I even support their aims in general terms. Yet, I many times saw that movements (lead by foreigners, but also city-Portuguese) side-line or criticise locals, instead of trying to get under their skins (looking back to the place’s history) or even learn from them (about the place stories, customs and practices).

I know that practices rooted in local culture are sometimes not sustainable. Yet, I think that newcomers (both foreigners or Portuguese) could at least try to incorporate the stories (and the practices when possible) of the place within their projects so they don’t become forgotten, but also to be fair to the difficult past and present of inhabitants of the interior Portugal. This is by no means easy, it requires time, resources and good empathy, but it would make these sustainable driven project a success in broader terms, not only within their land.

Sources

Diprose, G., 2016. Negotiating interdependence and anxiety in community economies. Environ. Plan. A 48, 1411–1427. doi:10.1177/0308518X16638659

Diprose, G., Dombroski, K., Healy, S., Waitoa, J., 2017. Community economies: Responding to questions of scale, agency and indigenous connections in Aotearoa New Zealand. Counterfutures 167–183.

[i] As a remnants of the Germanic property system, Galicia (Spain) and Portugal have a property regime called baldio based on usufruct: only if one needs land, when one uses it for survival and thrive of its community, then one can have rights towards it. In simpler terms, you borrow it while you live there, but leave it for others when moving somewhere else or die.