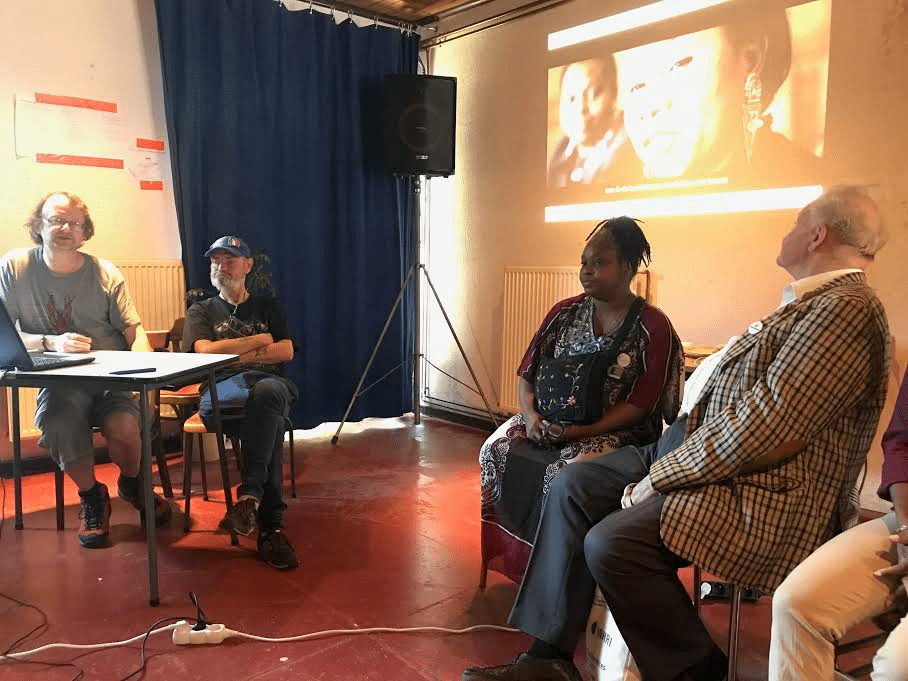

Participatory Video on the lives of homeless people in Belgium, screened at the Participatory Video Festival #1. Photo by Catia Rebelo.

Participatory Video on the lives of homeless people in Belgium, screened at the Participatory Video Festival #1. Photo by Catia Rebelo.

Although there is a growing interest in participatory visual methods, these are still far from being ‘conventional’. This brings some challenges, especially to PhD students. Therefore, a group of PhD students from Ghent University, Belgium, decided to create a space for reflection and bring together academics and non-academics that are interested in participatory visual methods. The first Participatory Video Festival took place in May 2018 and was held at De Koer, an arts hub reclaimed by the local community to support art related initiatives. The aim of the Festival was “to push the Participatory Video agenda”, a goal that I clearly support.

Indeed, as I am using collaborative visual methods the Festival seemed to be an excellent opportunity to share my work with like-minded fellows and, at the same time, to learn about the method’s challenges and strategies to overcome it. So, I decided to enroll my documentary and take part in the festival. I am glad I did it, and even more glad that my work was selected; according to the organizers they could only select 20 out 80 applications. I’d never thought that participatory visual methods were so popular and even the organizers hadn’t expect so many applications. I believe his is really good news and it gives me extra energy to keep advocating for visual methods as a valuable and widely accepted research technique.

What do we mean by participatory video?

One of the topics discussed at the festival was, what exactly do we mean by participatory video in academia as well as outside academia. Even though this topic has been greatly discussed in disciplines of visual anthropology and sociology there were some differences in how the term is being applied by academics and non-academics. However, in general means that the researcher hands over the control of the camera to the community that is being studied. In other words, the community is in charge of the video production, monitoring and evaluation. As this is a blog about visuals, find below an interesting animation, that in my opinion explains really well what participatory video is.

As you can see in the animation, participatory video brings a lot of advantages but also a number of challenges that may difficult to overcome for a PhD student with no visual background. Indeed, this method is very time consuming and requires a certain level of visual skills or collaboration with partners who are willing to use this method. Which may be difficult to find due to the “lack of visual quality” these works generally mean. I came from a tourism background and learnt some basic visual methods in my secondment at Binaural-Nodar to develop my research. Saying that, I was not confident to teach others how to use cameras, then many of my participants were seniors and did not feel comfortable handling cameras. I did not have enough material neither enough time, since I decided to focus my research on two different case studies, in which I co-produced two twin-documentaries. Therefore, instead of using participatory visual methods I am using collaborative visual methods. What means, that in my research participants did not film the documentary themselves, but I tried to make it as participatory as possible.

I developed individual interviews and focus groups in which participants had the opportunity to check and reflect on the accuracy of the narrative that was being co-created as well as decide if they would like to share it and with whom. The focus group created a space for reflection about what place means for all participants and lead to participants’ agency and capacity to develop a better place, what generally is one of the aims in participatory video.

Others like me adapted their participatory videos to their own specification and limitations. For example, the photograph at the start of this blog illustrates a very powerful film about the right of habitation of homeless people in Belgium. From the left to the right we can see the filmmaker and the film participants. The film is always screened with some of its participants who share insights about their lives and how important the film was for them.

Interesting food for thought

At the festival we also discussed how important reflexivity is in participatory visual methods. If you are thinking of using visual methods, here are some of the questions on which we reflected during the festival.

- Why do I want do this research? Why do I want this video?

- What is the researcher’s role in the video production? Am I a facilitator, an editor or and an activist?

- What is the best way to tell this story? Who owns the story? Who is creating the story?

- Does it represents the voice of the community? Whose voices are being communicated? How can I possible represent the community in a short-video? Is it my interpretation of the community story/stories?

- Whose agenda is behind the story? Is it a political tool? Is it a way of gaining access to a community? Is it a way of giving back to the community? It is new knowledge?

- What kind of impact do I want to achieve? Who are my target audiences? Is there a concern about what the public wants to see?

These and other issues will be addressed in a position paper on using visual methods, that I will write in the near future as I am almost finishing my second documentary in the Brecon Beacons National Park, Wales. One of my next posts will be a reflection on the development of this documentary, so stay tuned!

If you wish to read about visual methods, I recommend ‘The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods‘.